Rudolf Steiners "Philosophy of Freedom" as the Foundation of Logic of Beholding Thinking, Religion of the Thinking Will, Organon of the New Cultural Epoch

Volume 2

Part VI. The Concept (the Idea) and the Percept (Experience)

1. The Three Worlds

2. The Genesis of the Concept

3. 'Sensory Appearance' and 'Thinking' in the World-View of Ideal-Realism

4. Goethe, Hegel and Rudolf Steiner

5. The Natural-Scientific Method of Goethe and Rudolf Steiner

6. The Subject of Cognition

Chapter 4 – The World as Percept

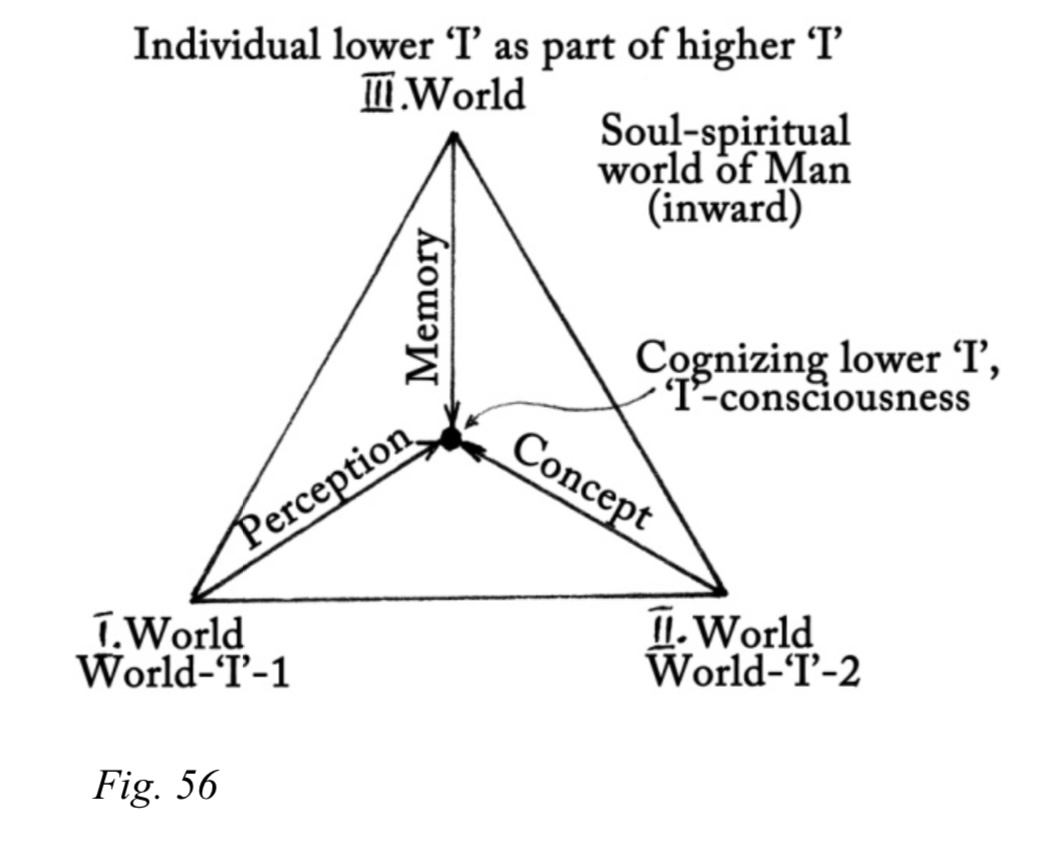

The experience of knowledge which we have acquired as a result of our work with the first three chapters of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’, allows us to make certain generalizations. The conscious being of man stands before us as an activity that is carried out at the meeting-point of three worlds, each one of which has its representation within the cognizing ‘I’. Thanks to this fact the latter has in the human being the character of a self-conscious principle.

The first of these three worlds is the sense-world, given to us in (outer and inner) percepts. The second world is thinking. In its essential nature it stands beyond subject and object. The phenomenon of thinking in man is merely a special case – albeit one of immense significance – within the total structure of the universal being of thinking. This world will, more than once, be an object of our discussions, but for the present we will “make do” with a general characterization. The universal world of thinking is the primal source and the ideal foundation of all being. In its manifestation before created things it was (and remains) the world of (in the view of Scholasticism) the essential intelligible beings, the thought-beings. Concepts and ideas serve as the representatives of this world in human consciousness.

With the accumulation of (pure and empirical) knowledge there emerges in the human being a soul world of his own which sends its representatives in the form of memories into the active life of the human spirit. This world stands as a subjective one over against the objectivity of the first two worlds. For the becoming of the human ‘I’, all three worlds are equally indispensable. If any one of them is excluded, the human individuality simply does not come into being. The consequences arising from this are many and various. Firstly it gives us full justification in asking: If the existence of the human individuality has an objective character, is it possible to exclude it and to regard the first two worlds as fully existent nevertheless? If not – and this is the second point – can one then regard the phenomenology of the human spirit as being without foundation? Do we have the right to dispute the fact that the conceptual expression of the world-intelligence in man is an objective process which constitutes a part of the world process as a whole?

The answer to these questions can provide the solution to the riddle of the human being, and it can be found through spiritual-scientific study of the genesis of world and man.

In the sphere of

soul-spiritual processes, the ontogenesis,

within the subject, of its ‘I’-consciousness, is

of decisive significance. As we have already

described, this ‘I’-consciousness is supported

upon the reality of the three worlds, where the

percept plays the role of “prime mover”. It

calls forth of necessity in the subject – so we

read in the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ – the

manifestation of the corresponding concept,

which arises from the world of thinking. Their

union gives rise to the inner representations as

the content of the individual spirit (mind).

They accumulate within it and, through the

cognitive activity of the ‘I’, are brought

together into the system of a world-view

(Welt-anschauung) – thus providing the basis for

the motives of activity.

All this can be shown in its entirety in diagrammatic form (Fig.56). As all that is real in the world is personified, we must imagine behind the three worlds which are the object of our study, the presence of creative ‘I’- beings through whom their selfhood and their self-development are conditioned. Behind the world given to us in percepts (the sense-world) there stands the ‘I’ of the universe. But this also stands behind the world of thinking, which is none other than the universal individual (see Figs. 17 and 25a). In relation to the cognizing subject the ‘I’ of the universe appears in two aspects: outwardly (‘I’-1.) through perception, and inwardly (‘I’- 2.) through thinking. The ‘I’ at the apex of the triangle and the ‘I’ at its centre are one and the same – i.e. the lower ‘I’ of the individual, which is in a process of development. But there are also differences between them. The ‘I’ in the centre is the one that is decidedly the lower; the ‘I’ at the apex is in touch with the higher ‘I’, which is becoming individualized in the human being and which exists (and is active) potentially behind the spiritual world of the human being and makes its presence felt in him from time to time; thanks to it, or within it, there also takes place the process of the “gathering in” of the personality, its involution.

In the early stages of the objective evolution of the human monad, its involution had an entirely substantial character: As the Hierarchies thought the human being, they created his triune corporeality. In the first stages of the development of ‘I’-consciousness the thought-pictures experienced by the human being also influenced his corporeality fundamentally, but especially the substances of his soul-body and his sentient soul. All this had a decisive influence on the character of the different religious beliefs and rituals and the modes of upbringing and education. Depending upon which Gods men worshipped, different types of personality developed among them; this even found expression in their outer appearance: there was the Apollonian and the Dionysian. One may confidently assert that also the racial differences between human beings are determined by their traditional, age-old forms of religious belief.

Something else emerges in the human being in the process of his individual evolution. The situation here is that, once we have become ‘I’-beings, we experience how the percepts give us the stimulus to the forming of concepts, but as yet we are not able to create conceptually, out of the ‘I’, a sense-perceptible object. Where our inner world is concerned, however, the complete reverse is true: the objects of perception within it (memories) can only be brought forth

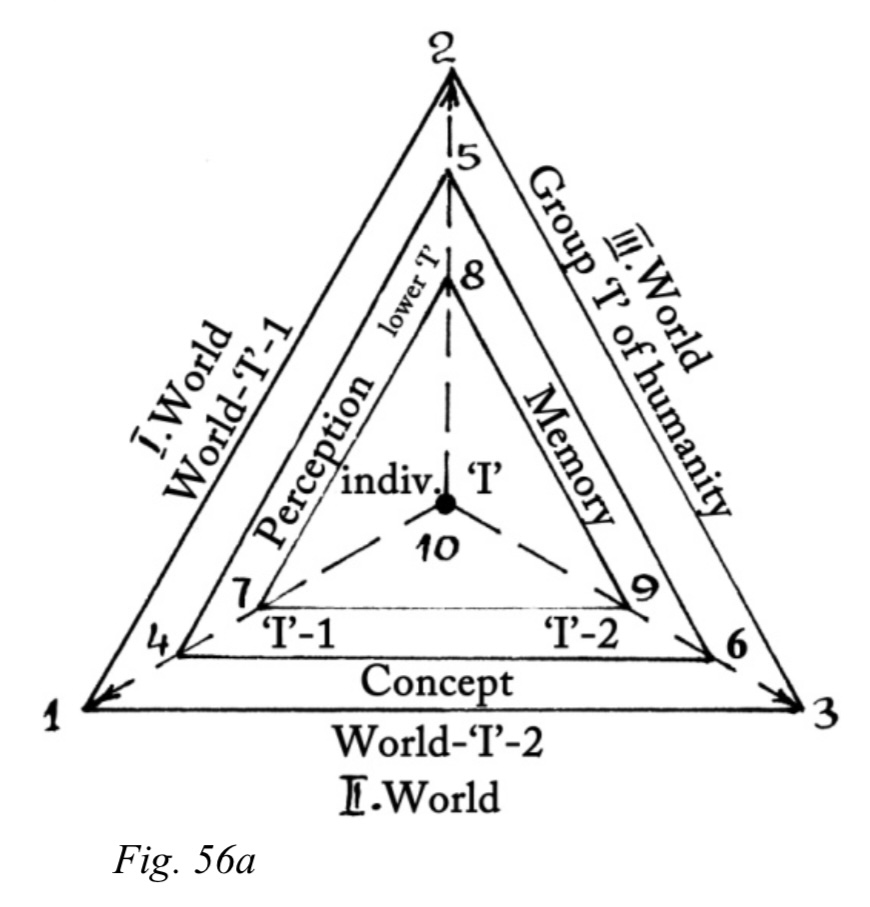

through the conceptual, thinking activity of the ‘I’. We can only estimate the significance of this fact rightly, if we understand the human being as the unity of ‘I’ and the world. This is constituted through the totality of the three tri-unities, and consisting of 3 x 3 elements, which draws together the dynamic of the ‘I’-consciousness into a single whole, a system, the dynamic of the ascent from the lower ‘I’ to the higher ‘I’ (Fig.56a). Thus the human individual incorporates himself into the world-individual, grows into it, enriches it with the qualities of self-conditioned self-development under the conditions of free choice between being and not-being, between good and evil.

Within each of the tri-unities represented in the Figure, the elements of which they are composed can be regarded as identical in nature. In the process of the involution of the human spirit they form a hierarchy. It passes through this hierarchy in the process of its individual evolution which leads it via identification with its elements. In this case, progress is determined through the striving of the lower ‘I’, which is able to condition itself as it grows upwards into the higher ‘I’; then the concepts become identical with the percepts and memories. Potentially, within the system of tenfold man, all three ‘I’s of the inner triangle are identical.

In his characterization of Saint-Martin’s ten-leafed book Rudolf Steiner says that the main page in it is the tenth; without this, “all the preceding ones would be unknown.... the Primal Creator of things (but this is what man, too, must become – G.A.B.) (is) invincible by virtue of this tenth page, because it is a corral (a circle of wagons – Trans.) around him, through which no being can pass” (Beiträge 32. p.13). The tenth page forms the corral – to speak in the language of methodology – simply through transforming the structure of 3 x 3 elements into a unity, a system, thus leading them back to that from which they sprang – the original unity, the Creator.

In the case we are

considering, the “corral” of the system of nine

elements has taken on the character of a

“fortress” consisting of three sets of walls.

Behind these walls the true ‘I’ of the human

being matures in its sovereign independence,

whereby it bears the character of an active

centre of transformation. Its “security” is not

assured through isolation from the world, but

through a lawfully structured dynamic connection

and interaction with it. This is something like

a state of “active defence” – a victorious

resistance struggle of selfhood and of the

maturing of the lower ‘I’ to the higher ‘I’

within the organic totality of the three worlds.

Here the outer antithesis to God (in concept and

percept) is transformed into the supremacy of

God in the holy of holies of the individual ‘I’.

Thus is realized the word of St. Paul “Not I,

but Christ in me” – the higher principle of

human freedom. Its stages are as follows: First

the ‘I’ in its separation from the Divine world,

then the sacrifice of the (lower) ‘I’ in Christ

and, finally, resurrection in the higher ‘I’.

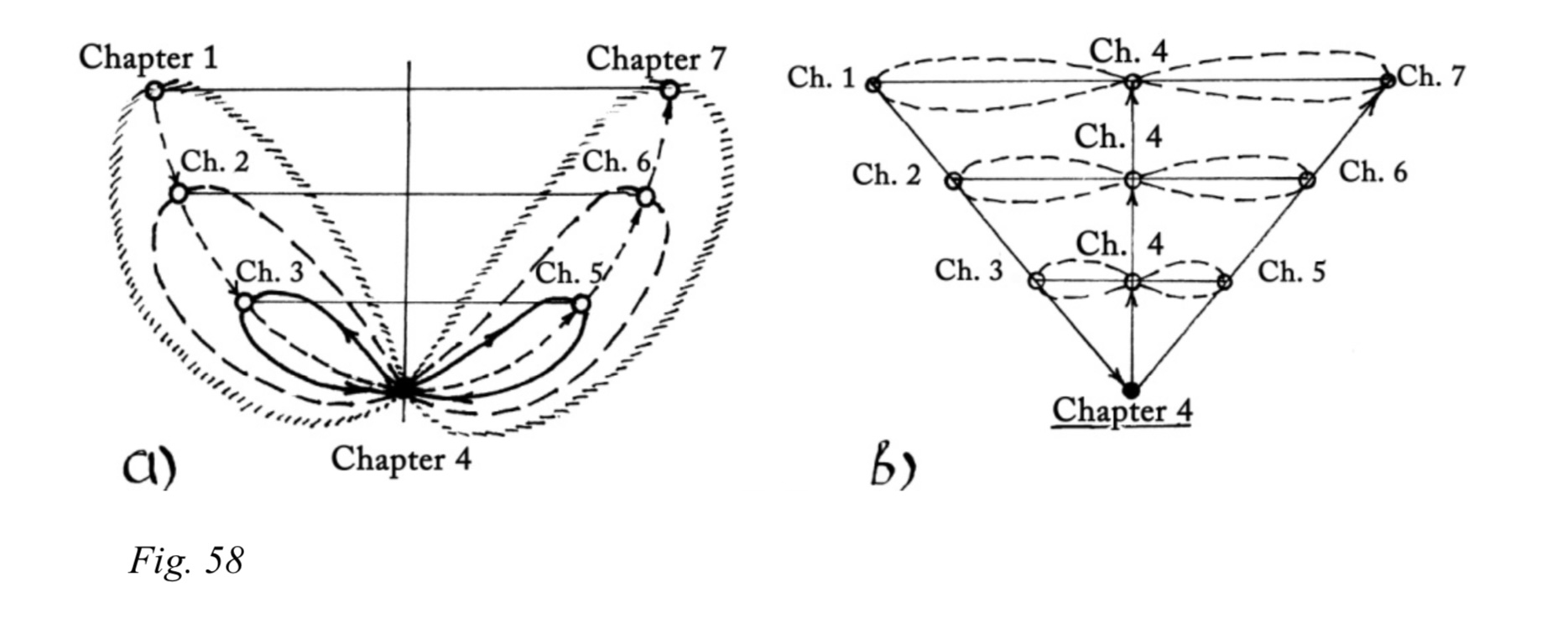

In the considerations

that are summed up in Fig.5, we showed, from the

cultural-historical aspect, the general

principle of the acquisition of the concept by

the human being. We will now go on to examine

the nature and significance of concepts, and

their place within the structure of the unitary

soul-spiritual entity man-world.

Rudolf Steiner describes the genesis of the concept in close connection with the process of man’s development in the course of the culture-epochs. All that occurred before them belongs to the cosmic “biography” of the concept, which could tell of the stages in world-development where the human being was no more than an object among many others.

In the first culture-epoch of our root-race, knowledge still flowed into the human being, as it were, directly from the spiritual world of imaginations. The purpose of the word was to evoke within the soul living pictures of what was knowable, and convey them to another soul. At that time no logic was possible. In the Old Persian epoch human beings also received concepts by way of supersensible mediation, but experiences of the sense-world began to determine their form. The Egyptians were the first to begin to apply concepts to the needs of the physical plane – in astrology, in surveying, in building. Concepts were given the form of symbols, but their supersensible substance withdrew from the human being. The fullness of the supersensible was experienced by the Egyptian in the form of a triangle, and he therefore experienced himself, – as a creature, a vessel of God – also as a tri-unity (see GA 124, 7.10.1911). In the Ancient Greek epoch man grew conscious of the fact that, when he gains knowledge of the world, he adds something new to it, and that in his thinking he is disconnected from the world. This began with Aristotle. Later, in the Middle Ages, the need arises to apply Aristotelian logic to the world-processes and thus grasp their nature by way of the intellect.

Socrates and Plato were the first thinkers who, instead of symbolizing the perceptions of the supersensible, transformed them into concepts. Aristotle developed the conceptual activity of the spirit (mind) and attempted to apply it to knowledge of the sense-world, within this world itself. It was not long before the agonizing question arose: Is knowledge of this kind able to bring us into connection with the original foundation of the world? (Scepticism – Pyrrho, 360-270 B.C.) The agnosticism of our time has its roots in the skepticism of the Ancient Greeks.

Anthroposophy brings

the human being into a relationship to the

concept, such that on the one side of it he

meets the sense-world, and on the other side the

spiritual world. One should beware of

immediately seeing in this position an appeal to

the mysticism of neo-Platonism. Conceptual

thinking is regarded in Anthroposophy as an

organism; it grows and embraces the soul in the

complete fullness of its life, not closing it

off in abstraction but, on the contrary,

enriching it with the reality of the world of

spirit.

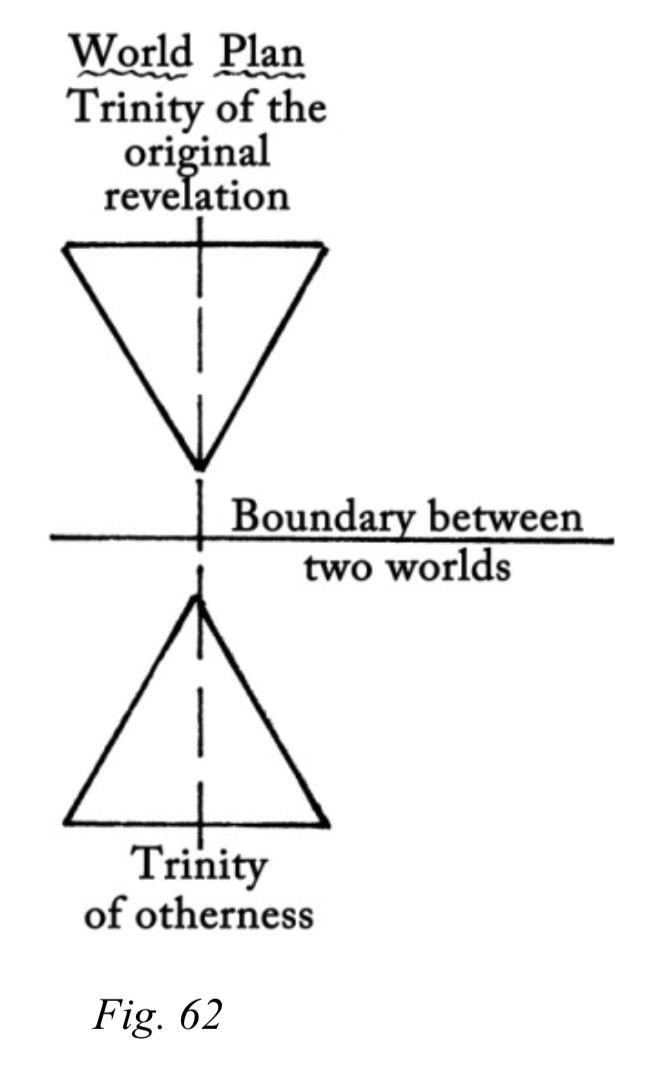

In his account of the nature of the concept, Rudolf Steiner suggests that we imagine an object that is blocking the path of the light and casting a shadow. This shadow is similar to the object in question and comes about because the light is shut out from a given volume of space. Something comparable to this phenomenon happens with concepts. When they are formed, a certain supersensible reality is shut out, and the concepts – like the shadows – resemble them, their “objects”. Hence, they bring to manifestation the supersensible in the sensible world, albeit in a very remarkable way. Where perception of the super- sensible shifts over into the sense-world a shadow-picture arises – the concept. There is contained in it as little supersensible reality as there is sense-reality, sense-perceptible object, in the shadow. The concept represents the boundary between two worlds, but this boundary is “drawn” from the side of the supersensible world.

When we think dialectically, we connect concepts with concepts, whereby we follow the law of their autonomous movement (in the way Hegel did). This law of theirs is a manifestation of the supersensible reality standing behind them. The concepts themselves embody so fine a material substance, that they are the most spiritual of all that man calls his own in the sense-world. It is not at all easy to grasp the super-sensible nature of concepts and ideas, yet it is in the highest degree necessary; the crisis of cognition bears eloquent witness to this need. We can be helped in this undertaking by the evolutionistic research method of spiritual science.

* * *

The objectification of concepts, their severance from their connections with the world-whole, occurs not only by way of the cultural-historical process of development. This separation is prepared for by the spiritual-organic becoming of man, which, projected onto the cultural-historical process, continues right up to the present day, albeit in a weakened form. Its peculiar feature consists in the fact that, as it unfolds, as Rudolf Steiner says, “a non-being in thinking” is released from sense-perceptible reality (B. 45, p.12).

From the mid-point of the earthly aeon, which coincides with the middle of the Atlantean root-race, universal consciousness separates off a part of the world-whole and sets it over against itself in the sphere of otherness, as a kingdom in which the life-principle (etheric principle) is absent. Finally there takes place a “separating off” of consciousness itself into the sphere of non-consciousness, if one regards consciousness from the standpoint of real being.

* In the books and lectures

of Rudolf Steiner all these processes are described

from many angles and with a wealth of detail

______

Rudolf Steiner describes this transition as follows: “But just as in the head there is taken up by the sense-perceptions the breath-process that streams into the body, so is taken up by the rest of the body that which streams outwards as outbreathed air. In the limb-metabolic organism there stream together the bodily feelings, our experiences with the outbreathed air, just as the sense-perceptions stream into the head through what we hear and into the exhilarating element of the inbreathed air through what we see. The sobering quality of the outbreathed air, that which extinguishes perception, all this streamed together with the bodily feelings aroused by walking and by work. Doing things outwardly, actively, this was connected with the outbreathing. And as the human being engaged in activity.... he felt as though the spiritual-soul element was flowing away from him.... as though he was letting the spiritual-soul element stream into the things. .... But this perception of the outbreathing.... of the sobering process came to an end, and there was only a trace of it left in the Greek times. In Greek times human beings still felt as though, when they were outwardly active, they were giving something spiritual to things. But then all that was there in the breathing process was depleted by bodily feeling, by the feeling of exertion, of tiredness in work” (GA 211, 26.3.1922).

The inbreathing process was “impaired” in the head, and what was left of the former inbreathing process which led into the spiritual and had then been “impaired” by the outer sense-perceptions, one began to call “Sophia”; those who wished to devote themselves to this Sophia were known as philosophers. The word “philosophy”, so Rudolf Steiner remarks, points to the “inner experience”.

The outbreathing process which was “impaired” through the feeling of the bodily nature became “pistis”, faith. “Thus wisdom and faith flowed together in the human being. Wisdom streamed to the head, faith lived in the whole human being. Wisdom was the content of ideas, and faith was the strength of this ideal content.... In the Sophia one (had) a rarefaction of the inbreathing, and in faith one had a densification of the outbreathing.... Then wisdom was rarefied still further. And in this extended rarefaction wisdom became science” (ibid.).

The process described by Rudolf Steiner took many thousands of years; it was accompanied by a whole series of physiological and other processes, a particularly important role being played here by the acquisition of the power of speech. When man did not yet have the power of articulate speech, he was able to understand the sounds of nature. This was in the Old Atlantean epoch. After that time the half-supersensible perception of the language of nature grew ever weaker. The human being developed speech organs, acquired the gift of speech and began to understand the meaning of words, and this is ultimately what drove the “ash” “physically-chemically” into the elements of his body. The bony skeleton began to form in the body, and as this emerged, so the intellect began to dawn. But before all this happened, the coarsening of perception which occurred in the Lemurian epoch after the opening of the sense-organs to the external world, brought with it a qualitative decline of the processes in the circulatory system of the blood. The nervous system, too, became mineral, “physical-chemical”, but as this happened it took over the former spiritual breathing – astral breathing. Because sense-perceptions had grown unusually strong, their influence caused us to lose the faculty of experiencing the breathing process consciously. In ancient times the human being, when he breathed in, perceived within himself the spiritual content of the object and carried out his observation in this way; in his outbreathing he surrendered the feeling of the spiritual and felt within himself a strengthening of the will-impulse – he carried out an action. Today, the impulse of outer perception, through stimulation of the nerve, reaches through to the blood circulation and has an effect upon it, which then passes over into the whole organism, including the metabolism. A portion of the material substance falls out of the organic process and the life of the inner representations arises as a result.

A yoga pupil attempts to restore to the breathing process its ancient function, to make it conscious, free from the forming of sense-impressions and, using the breath as a vehicle, to reunite in spirit with cosmic wisdom – “to become one with Brahma”. But the human being of the West, says Rudolf Steiner, has all of this “already in his concepts and ideas. It is really so: Shankaracharya would present to the pupils who revere him, the idea world of Soloviev, Hegel and Fichte as the beginning of the ascent to Brahma” (GA 146, 5.6.1913).

On his descent into earthly incarnation, the human being forms himself out of the forces of cosmic thought. But on the earth the universe surrounds him with sense-impressions and lives reflected in his thinking. The outer world in its influence upon man tends to condition and compel him in the same way as, in the past, he was influenced by spiritual-supersensible forces. If the human being were merely to reflect the outer world, he would be subjected by it to the laws of its inorganic realm, in which the laws of the universal spirit come to expression (are reflected) in the most ideal way. In such a case, says Rudolf Steiner, our lungs, convolutions of the brain etc. would have assumed crystal-line form. But the life of our organism opposes such tendencies. “And this activity of resistance accounts for the fact that, instead of imitating with our organs the forms of these earthly surroundings, we merely copy them in shadow pictures in our thoughts. Thus the power of thought is actually always tending to make of us an image of our physical earth, the physical form of the earth. ... But our organization does not allow this to happen...and so the images of the earthly forms only come about in geometry and whatever else we form in the way of thoughts of our earthly surroundings.... A table wants to make your brain itself into a table inside your head. You don’t allow this to happen. Thus arises within you the picture of the table” (GA 210, 17.2.1922).

* * *

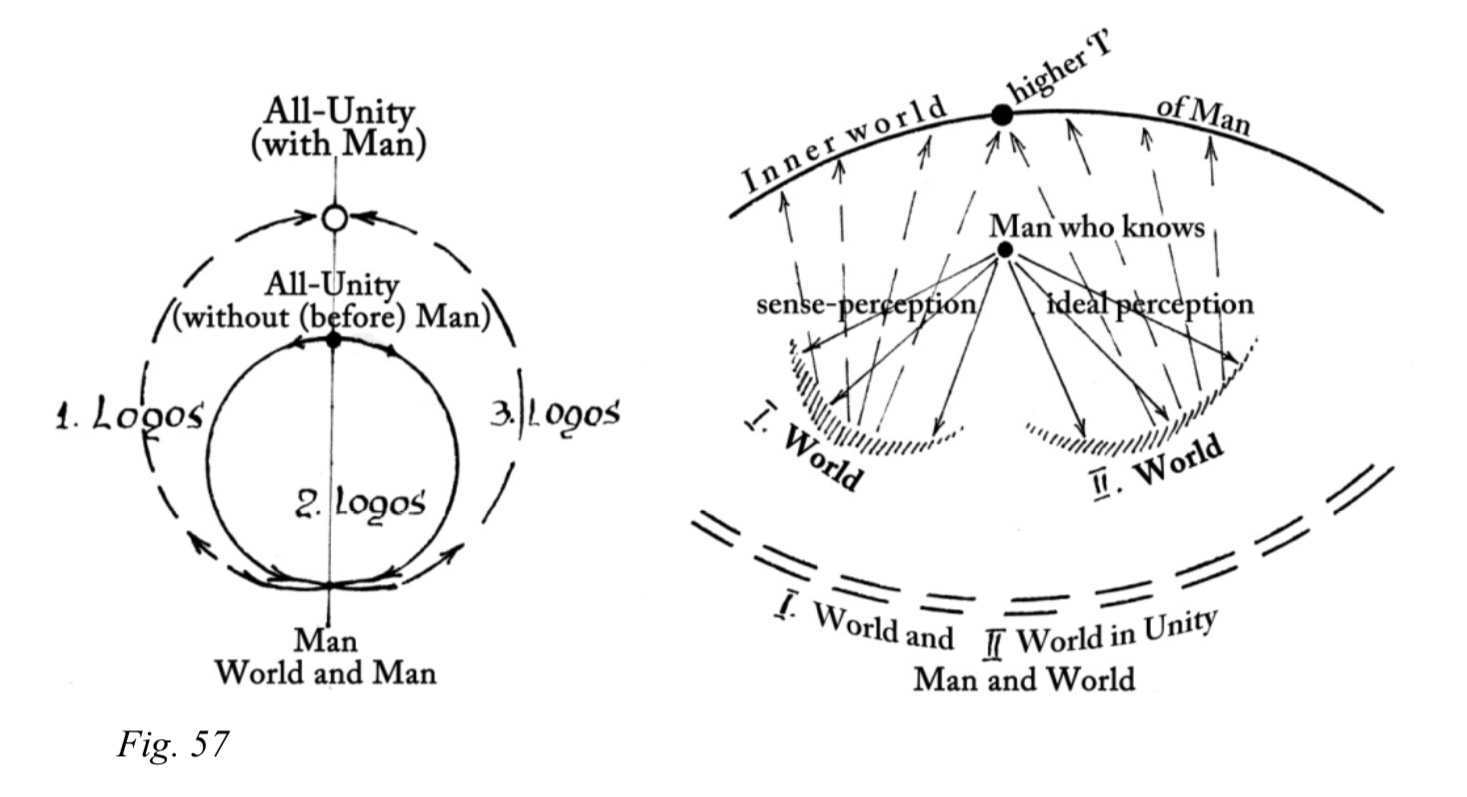

Such is the interrelation of the two sides of reality, and their effect upon the human being who is placed between them in his earthly life. From this knowledge we can draw an understanding of the nature of human self-consciousness and of the self-conditioning capacity of the human being. Here the macro and micro-levels of being stand in the most direct mutual integration. In order to grasp their interplay as it is at the chronologically latest stage, we must look back at their primal origin, which we did in our account of the first act of the creation of the world by the three Logoi. When God had revealed Himself in three hypostases, He showed His counter-image in the creation. A process of ‘inwardization’ of the Creator in the creation took place, which was also the primal origin of the development of inner processes in the created world. Fundamentally speaking, the cosmos ‘inwardized’ itself in the processes of the human blood and nerves. The Divine will to sacrifice, to revelation, which created all the visible forms in the universe, brought about, after He had become, within the subject, absolute desire of (for) selfhood, that inversion which made the human being into an image in miniature of the cosmos – the microcosm.

Without radical opposition such a process is impossible. The Divine will which, in the human being, in his willing and feeling, sets itself over against itself, becomes desire and takes on an egocentric character. To a certain degree this robs the creation of its meaning; it begins to die, to be shed like withered leaves from the universal reality. It is not easy to imagine how the egocentric tendencies of the human monads led to the emergence of the entire universe that is visible to the senses, but it is nevertheless true. Before it acquired individual ‘I’- consciousness the human monad was a macrocosmic being. It was a combination of different strivings of hierarchical Beings, whose shared goal it was, to create the ‘I’-being in the world of otherness. From a certain moment in development (it is marked by the Fall from Paradise) the human being was driven by desire – which became within him a Luciferic will to act – uncontrollably into the world of otherness (of not being), where finally the abstract concept was born – the form of consciousness which had entirely lost the relation to its spiritual, cosmic archetype. Intellectual thinking represents, as it were, “holes in the universe”. And when I think, says Rudolf Steiner, this means that I am not (cf. GA 343, p.434). In this state of being a strong individual will can, of course, arise; desire that is purified and freed from Luciferic arbitrariness is transformed into will of the individual spirit to attain freedom. And because, if we think in concepts, we dwell in the realm of non-being, there also arises in the universe a place for freedom of this kind, for the free motives of human activity.

With his concepts that are devoid of essential being, the human being was cast out to the periphery of the universe. There, particularly from the 15th century onwards (from the beginning of the consciousness-soul epoch), concepts lost the final traces of their perceptual character. Since that time one can restore it to them only by bringing the will into the thinking and into the process of sense-perception. The passive beholding of the imaginative world of the thought-beings by the Ancient Indians, which in the Egyptian passed through the stage of spiritualized thought-perception of the macrocosm, of its universal laws and their projection onto earthly being, became in the fifth cultural epoch the mathematical-mechanistic conception of the world (but beyond these conceptions the real world of cosmic thinking can open up to the human being). Having, himself, become ‘not-real’ in thinking, the human being attains a free relation to the real as to the object. One of these objects is he himself – the active object of self-knowledge. And “to know oneself as a deed-performing personality,” so Rudolf Steiner says, “means: to possess as knowledge the laws – i.e. the moral concepts and ideals – which correspond to one’s deeds. Once we have attained knowledge of these laws our action is also our own.... The object in this case is our own ‘I’.” Rudolf Steiner concludes from this: “To know the laws of one’s own action means to be conscious of one’s freedom. The cognitive process is, according to the argument presented here, the process of development to freedom” (GA 3, p.87 f.). There arises thus between the laws of pure spirit and the natural laws of the sense-perceptible universe, the world of the laws of the self- conditioned human individuality. As we are bringing to light the true nature of cognition in this way, we would also recall that the unitary foundation of being is shown to us in a threefold revelation: As the world of perceptions (both outer and inner), as absolute desire and as the world of thinking, in which the Holy Spirit strives to reflect back to the Father, in a pure form and in the ‘I’, the principle of His universal consciousness. Hence there is revealed in thinking that has freed itself from percepts in which the sense-world imposes its forms upon us, the entire foundation of being “in its most perfect form, as it is in and for itself” (GA 2, p.84). When we think, the Divine Ground of the world merges immanently with the process of thinking. It works within it not out of some kind of world beyond, but immediately, as within its own content. Over against this content of the Divine Ground there stands the world of experience as Its own manifestation, mediated by the process of development. A first consequence of this is, that “Through our think- ing we raise ourselves from the beholding of reality as a product to the beholding as a productive fact” (ibid.). A second consequence is that in the human being and through him God cognizes Himself in the act of creation.

Through acquainting himself with the laws of thinking and using them in his activity, the human being overcomes the death quality of the isolated concept. He brings dynamic into concepts, leads the one over into the other, metamorphoses them. Thus he awakens an – albeit still illusory – life of the conceptually thinking consciousness. As an outcome of this there arises pure thinking, which is not only free of all sensory content, but is also freed from the human organization itself (see chapter 9 of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’). It is now no longer the same thinking as that which had as its content the sum of the concepts called forth by perceptions. It frees itself from all experience of whatever kind, in order to reflect it back to the Father in the hypostasis of the Holy Spirit. Since it is a fruit of evolution, the whole of evolution is present within it in a preserved and yet superseded (aufgehoben) form: evolution constitutes its essential being. But essential being is always the ‘I’.

* * *

We have thus arrived at a kind of cyclic movement in the development of world and man. At its beginning, God, revealing Himself as three in one, gives the impulse, as an all-embracing idea of creation, to a cosmic cult in the course of which the higher Hierarchies who fulfill the will, the idea, of God offer up in love the gifts of sacrifice one after the other. The fruit of these is a new phenomenon in the universe – the human being. The world-idea is then incarnated in the human being. At the beginning of the earthly aeon the Holy Spirit, working through the creation to the Creator, brings about a ‘separation’ of sense-reality from man. This reality, at a later stage, confronts him from within and without in a form that grows increasingly complex. For this reason, as Rudolf Steiner says, everything that we rightly describe as our inner world also stands over against us in the outer world. All that we can experience inwardly is experienced by us together with (in connection with) the entire external world (see GA 191, 18.10.1919). We reflect thoughts, but the entire material world given to us in sensations and perceptions reflects our perceptions. In relation to us it is entirely similar to the brain, and we enter into a relation to it in the role of thought-beings, who use the support it provides and are reflected back from it through the astrality of our perceptions. ‘Thinking’ of this kind (external to ourselves) is not abstract; it is living and substantial, but not individualized like our conceptual thinking. As his ‘I’-consciousness grows in strength, the human being frees himself from this thinking of a super-individual, group nature into the non-being of abstractions. And yet their world possesses something that is, without doubt, of decisive importance for man. Rudolf Steiner speaks of this as follows: “As we only experience in thinking a real, lawful structure, an ideal determination (ideelle Bestimmtheit), the lawful structure of the rest of the world which we do not experience directly within this world, must also be contained in thinking. In other words: appearance as phenomenon for the senses and thinking stand over against each other in the world of our experience. However, the former provides us with no insight as to its essential nature; while the latter provides us with insight as to itself and, at the same time, as to the essential nature of the realm of appearance for the senses” (GA 2, p.48).

In other words, the essential nature of the thing can only be known through the thing being brought in relation to thinking consciousness. And the essential nature of the thing is the embodiment of the world- idea. To imagine that ideas exist in the heads of human beings is an illusion pure and simple. No, they hold sway as laws within the things. The Anthroposophical theory of knowledge maintains the standpoint that the universals of three kinds are merely different aspects of a single Idea. The division of the world into object and subject has, therefore, no more than a formal character. “The idea conceived by the primal Being could only be one that, by virtue of a necessity lying within itself, develops from within itself a content which then manifests in an- other form – in a ‘beheld’ form – in the world of appearance” (GA 1, p.108). The two forms of manifestation of the idea (as concept and percept) attain their full congruence in the human being.

3. ‘Sensory Appearance’ and ‘Thinking’ in the

World-View of Ideal-Realism

The belief that the world is hopelessly divided for the cognizing subject into inner representation and ‘thing-in-itself’ has its source in religious and moral convictions of ancient times. It originates in that conception of development which is described figuratively in the Bible as the story of the Temptation and the expulsion of man from Paradise. It was at this time that what amounted to a confrontation between creation and Creator took place, and this gave rise to the preconditions for a dividing into two, of the creation’s experience of the world. Considerably later, in the Zoroastrian religion of the Persians, man began to experience the dualism of the world as the opposition between light and darkness, good and evil. The consciousness emerged in man, of his participation in the cosmic battle between the good and the evil Gods. In the Ancient Greek culture-epoch the religious conceptions are given philosophical expression, whereby the darkness of outer, sense-perceptible being stands opposed to the world of ideas coming from above. Also coloured by the heritage of the past is the dualism of the Christian view of life, in which the world of sensory, material reality is brought into connection with the picture and the idea of darkness and of sin, while the world of the prayer-illumined individual spirit is connected with the idea of salvation, of redemption from sin.

The whole of this, in a certain sense, ‘inherited’ dualism is overcome in the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’, first on the philosophical and then on the moral level. The human being is led to experience of the unitary world when he acquires the conceptual, moral intuitions – i.e. when he radically alters, spiritualizes the way he observes. To a certain extent, a return to the old takes place, but on a different, individual basis. The new human being has achieved this, at the price of his real and complete expulsion from Paradise. The Ancient Greek, however, who knew of the intuitive nature of thinking and morality, was still standing at the boundary between Paradise and earth. Parmenides, the founder of the Eleatic school, wrote a poem about a poet who travels along the boundary between two worlds and, as he does so, listens to the voice of a Goddess. She teaches him that true being exists only on the other side of the boundary, and that being on this side of the boundary is necessary, but deceptive.

Plato shared the position of the Eleatics. He divided conceptions of the world into two categories: the true one, which seeks its support in the world of ideas, and the other, which in its nature is apparent only, being conditioned by what is given through the sense-organs. Awareness of the fact that the world is revealed to the human being from two sides had enormous significance for the further development of the ‘I’- consciousness, but in the history of the development of thought in Western Europe, an error which then became universal sprang from the world-view of Plato. It consisted in the following question: What is the nature of the relation between the sense-world and the world of ideas outside the human being?

In his book ‘Goethe’s World-View’ Rudolf Steiner characterizes as follows the consequence of Plato’s world-view mentioned above: “Platonism is convinced that the goal of all striving for knowledge must be acquisition of the ideas which carry and constitute the foundation of the world” (GA 6, p.28). A sense-world that is not illumined by the world of ideas cannot be regarded as full reality. This was then interpreted to imply that “the sense-world in itself, quite apart from the human being, is a world of appearance, and true reality is only to be found in the ideas” (ibid.).

This position was also adopted without reservation by Spinoza, who subscribed to the view that only those thoughts possess true reality which arise independently of sense-perceptions. He extended this to the sphere of ethics, the moral feelings and actions of man; he maintained that ideas drawn from our perceptions originate solely in desires. The ascetic ethics of the Christian religious consciousness, with which that of Spinoza was in full harmony, also stemmed from a one-sidedly interpreted Platonism. Incidentally, Spinoza found a brilliant way out of this tragic error. He had the idea that one could raise intellectual development to such a height, that the human being would begin to experience in thinking the real manifestation of the spirit. In his letter to H. Oldenburg written in Nov. 1675 one can read the following: “... I (say) that for the sake of salvation it is not absolutely necessary to know Christ according to the flesh, but that the case is quite different with that eternal Son of God – i.e. with God’s eternal wisdom, which has been made manifest in all things, and mostly in the human spirit, and above all in Christ Jesus.”132 Here we have to do with the Christianized theosophy of Plato. Quite a different path was taken by Kant, who definitively undermined all hope of knowledge of the essential nature of things. The knowledge we have, so Kant believed, is not of the things in the world, but only of the impressions which, in some mysterious way, they make upon the human being. The world of experience does not exist objectively. It is we ourselves who create the connections within it. There exist truths which are of significance for the world of experience, but which are not dependent upon it and are not able to re- veal to us the essential nature of things.

With regard to this world-view of the Königsberg philosopher, Rudolf Steiner said of him that he was lacking in “the natural sense for the relationship between percept and idea”. One of the prejudices taken over by Kant from his predecessors, said Steiner, consisted in his acceptance of the view “that there are necessary truths which are engendered by pure thinking, free from all experience”. In support of his claim that there are such truths, Kant pointed to mathematics and pure physics. “Another prejudice of his consists in his denial of the ability of experience to arrive at equally necessary truths. Lack of trust in the world of perception is also present in Kant. In addition to these habits of thought we must also count the influence of Hume upon Kant.” This influence showed itself in Kant’s sympathy for Hume’s contention “that the ideas into which thinking draws together the single percepts do not stem from experience; thinking adds them to experience. These three prejudices form the roots of the Kantian thought-structure” (GA 6, p.40 ff.).

Rudolf Steiner compares the mistaken conceptions of Kant with the views of Plato, summarizing them as follows: “Plato clings to the world of ideas, because he believes that the true nature of the world must be eternal, indestructible, unchanging and he can only ascribe these qualities to the ideas. Kant is content merely to be able to attribute these qualities to the ideas. Then they no longer need to express the essential nature of the world at all” (ibid. p.43). Kant’s teacher Hume, for his part, regarded human ideas as being no more than habits of thought (thus anticipating Mach, undoubtedly). For him, only perceptions possessed reality. A similar position was also taken by the sensualists John Locke and Condillac, and even by openly materialistic thinkers, from Lamettrie and Holbach onwards. The advance of Platonism in the modern age can be traced in a sequence of world-views extending from Spinoza to Hegel. For Hegel, thought-activity is an objective creation of the soul. Rudolf Steiner compares the role of Hegel in modern times with that of Plato in the ancient Greek period. Plato, so he says, “lifts his spiritual gaze to the world of ideas and lets this gaze in its beholding grasp hold of the mystery of the soul; Hegel lets the soul dive down into the world-Spirit, and then, after it has dived down, he lets it unfold its inner life. The soul thus lives as its own life what the world-Spirit lives into which it has dived down” (GA 18, vol. 1).

The whole world, so

Hegel believes, is filled

with the

Divine, i.e. with thought; God is an organism

consisting of the totality of all ideas, but of

those ‘before the things’ and not those that are

reflected back in the human head; it was, in

deed and truth, from the former that nature was

created; the human being developed on the basis

of this thought and it is his mission that in

him thought should be revealed in its highest

form – as the essential nature of things; the

evolution of the world, the history of culture

is ultimately nothing other than the development

of the idea: first of all in ‘being-in-itself’ –

i.e. before the created world, then in

‘otherness-of-being’ – i.e. in nature, and

finally in ‘being-for-itself’ – in the human

soul in history, in the State; in the highest

phase of its development the idea comes to

itself in art, religion and philosophy – in the

first two through the mediation of image and

symbol, but immediately in philosophy. “In

Hegel,” says Rudolf Steiner, “one can find a

pure thinker who wishes to approach the task of

solving the riddles of the world, by way of

reason alone, free of all mysticism” (GA 20,

p.49). He rejects mysticism as a source of

metaphysics, but only to let it rise up again in

the theosophy of philosophy.* Rudolf Steiner asks

what is the purpose, in Hegel, of “our life

in the ideas

of (pure) reason? It is so that the human soul

can submit in devotion to the supersensible

cosmic forces that hold sway within it. This

becomes a genuine mystical experience.... It is

mysticism ... when the soul wrestles its way out

of the darkness of the personal soul-life, up

into the luminous clarity of the world of ideas”

(ibid.). Nothing comparable to this can be found

either in Fichte or in Schelling – two of the

most notable representatives of German idealism.

But what unites them all is the striving to

confine themselves exclusively to the realm of

the conceptual. Yes, it is true that Hegel frees

logic, as it were, from the gravity of earth,

but it remains, all the same, a logic of purely

conceptual thinking and contains within it

nothing that would contribute to a stepping

across the boundary of the abstract into the

supersensible world of ideas, of which Plato

spoke. In his apologia of the world of thought,

so Rudolf Steiner tells us, Hegel actually

caused terrible confusion. He described “the

necessity of thought as being, at the same time,

the necessity of fact ... he thereby gave rise

to the mistaken view that the determinations of

thinking are not purely ideal, but factual”. But

one must emphasize, Rudolf Steiner continues,

“that the domain of thinking is

solely human consciousness”, but “this

circumstance does not cause the thought-world to

forfeit its objectivity in any way.... We must

imagine two things: one is that we bring the

ideal world to manifestation through our

activity, and that at the same time, what we

actively call into existence rests

upon its own laws” (GA 2, p.51 f.).

* Not, however, in the

philosophy of theosophy.

______

Anthroposophical philosophy shares the position of German idealism, but avoids its mistakes and enhances it through the addition of two essential elements. As to its mistakes, these are described by Rudolf Steiner with remarkable clarity and conciseness in one of his note-books: “Schelling was mistaken about nature, not because he sought the spirit in it, but because there is in it more spirit than he could find, because he tried to encompass the spirit of nature in the mere reflected image of the spirit, which lies in human thought. Instead of the beholding of nature – the creating of nature. (Schelling maintained that to philosophize about nature means to create nature – G.A.B.) Fichte was mistaken about the human being, not because he sought man’s essential nature in the act of self-willing, but because he was not able to let the whole human being arise out of the creative will, only the idea of the human being. – Instead of devotion to the world-Spirit – fetishism of logic” (Beiträge 30, p.19). With regard to the additional elements needed by Middle-European philosophical idealism, Anthroposophy sees the first of these in the solving of its own riddle. The representatives of what Rudolf Steiner calls the ‘forgotten’ streams of idealism came very close indeed to its solution. They included the younger Fichte, Immanuel Hermann (a successor of Schelling), the Swiss doctor and philosopher I.P.V. Troxler, Karl Christain Plank (1819-1880) and others. This riddle – or mystery, Rudolf Steiner says, consists in the fact that “German idealism...” points to “the germinal force of a real development of those cognitive powers in man which see the supersensible-spiritual just as the senses see the sensory material” (GA 20, p.63).

A further addition through which German idealism was enhanced by Anthroposophy consisted in the solution to the question how one should view the relation of the idea to sense-reality. Vast amounts of energy were wasted, especially in the school of Leibniz-Kant, in the search for a way to attain, in purely conceptual thought, knowledge of the essential nature of things without reference to the data of experience. Meanwhile, at the opposite pole of world-views, work was being done on the development of the experimental sciences – in which the human being was simply lost sight of – and of the philosophy of material immanentism, where everything culminates in the conviction: “Once man has researched all the properties of the material substances which are able to make an impression on his developed senses, then he has grasped the essential nature of things. He thereby attains what is for him – i.e. for humanity – absolute knowledge. For the human being, no other knowledge exists” (Jacob Moleschott, 1851). 133

In the final analysis, philosophy as a whole can be divided into two great trends, whereby the criterion one takes is the relation to idea and perception. One trend can be characterized as a kind of universal Platonism, which extends from its founder to the medieval mystics and classical German idealism and from there to the Russian Sophiologists (V. Soloviev, Andrei Beliy, Pavel Florenski etc.). Common to all these thinkers is the striving to help thought to achieve a position of domination. For them, knowledge of the idea is the knowledge (Wissenschaft) of what truly is. While one cannot say that these thinkers ignore sense reality, they do underestimate it and are often at a loss to know what to do with it.

The other fundamental trend in philosophy can be seen as proceeding from Aristotle. This is the stream of realism. To illustrate its essential character, we can refer back to what Rudolf Steiner says about Aristotle in ‘The Riddles of Philosophy’: “Aristotle wishes to dive down into beings and processes, and what the soul finds in this act of diving down, is for him the essential nature of the thing itself. The soul feels as if it has only raised this essential nature out of the thing and brought it into the form of thought, in order to be able to carry this with it as a memory of the things. Thus, for Aristotle the ideas are in the things and processes; they are the one side of the things, that side which the soul, through the means available to it, can raise out of them; the other side, which the soul cannot raise out of the things, and through which they have their own self-contained life, is substance, matter” (GA 18, vol. 1).

Aristotle develops the doctrine of the threefold soul. In this, he investigates – in contrast to Plato, for whom only that in the soul is important which, within it, lives and shares in the life of the spirit – how the knowledge it acquires stands over against the soul, and in a different way towards each one of its parts (this question is also dealt with by Rudolf Steiner). In his outline of the riddles of the ancient Greek philosophy, Rudolf Steiner says in this connection: According to Aristotle, the soul must “also dive down into itself in order to find within itself that which constitutes its essential nature.... The idea has its reality, not in the cognizing soul, but combined with the material substance (hyle) in the external thing. If, however, the soul dives down into itself it finds the idea as such in reality. The soul is, in this sense, idea, but active idea, it is effectively working being. And also in a human life it acts as an effectively working being. In the germinal life of the human being it takes hold of the bodily nature. Whereas in the case of an inanimate thing idea and matter form an inseparable unity, in the case of the human soul and its body this is not so. Here, the autonomous human soul takes hold of the bodily nature, makes ineffective the idea that is already active in the body, and puts itself in its place. ... A body that bears within it the soul nature of the plant and the animal is, as it were, fertilized by the human soul, and thus, for earthly man, a bodily-soul element is united with a spiritual-soul element. ... Aristotle finds the idea within the thing; and the soul attains within the body what it is meant to be as an individuality in the spiritual world” (ibid.).

The philosophy of Aristotle found its true continuation in Thomas Aquinas’ doctrine of the universals; when it became the foundation for the world-views that were dominant in the 20th century, it assumed a positivist and purely materialistic form. In time, the Aristotelian understanding of the material world as consisting not only of matter but also of substance, which underlies reality as a spiritual element, was abandoned as being no longer usable.

The world-views of idealism and realism in their overall phenomenology possess decisive significance for the development of the individual spirit to freedom. There comes to expression in them an orientation towards the higher ‘I’ and the lower ‘I’ (cf. Fig.35). In its movement towards the higher ‘I’, the individual spirit finds its true development, its truth, which is contained within the monism of ideal-realism. But in order to be able to reach through to this, one must first become familiar with its two component elements: the nature of human experience, which is given in the perception of the outer world, and also the inner world of the soul; and the (for the human being) deductive anticipation of experience in the world of the intelligible Beings.

4. Goethe, Hegel and Rudolf Steiner

Towards the end of the 19th century the maturity had been reached of the objective conditions for the uniting of the two general trends in the development of views of the world – idealism and realism. But first the capacity of consciousness to transcend the limits of the merely conceptual needed to be demonstrated through the medium of pure philosophy. Eduard von Hartmann tried to do this through an appeal to the unconscious, and Rudolf Steiner through an appeal to the super- conscious.

Already at the end of the 18th century, Goethe had been in a certain sense a precursor of the great synthesis. He understood that the question of the relation between idea and sense-world, of how the idea and the things of the senses can find one another – a question to which European thinkers had devoted so much attention – cannot be asked out- side the human being, but that their synthesis is only possible in the human being, and not by way of thinking alone or of observation alone.

The cognitive principle developed by Goethe rejects that part of Aristotle’s teaching which speaks of the attainment of self-knowledge through diving down into one’s own soul. Nor did Goethe wish to sink with his individual spirit into the world-Spirit, but only into the world of experience; for then, so he believed, one would also acquire the idea. For Goethe, the world of experience also contains within it the world of ideas; for this reason, so he asserts, it is incorrect to say “experience and idea”. Of course, the idea cannot be perceived with one’s ordinary sense-organs; it is accessible to spiritual experience, spiritual perception, but perception nevertheless, and in just as real a way as sense-objects are accessible to sense-perception. This was the view of Goethe, which formed the basis of his gnoseology and was so new that it was hardly understood by anyone until the end of the 19th century, when Rudolf Steiner gave a description and commentary on it, where-upon the scientific world treated it with barely concealed hostility.*

* Recently the plan has

been made in Germany to publish a new edition of

Goethe’s scientific works and replace Rudolf

Steiner’s commentary with an- other, thereby

obscuring Goethe’s method.

______

In his article ‘Concerning the Gain for our View of Goethe’s Scientific Work, arising from the Publications of the Goethe Archive’, which appeared in the 1891 edition of the Goethe Yearbook, Rudolf Steiner wrote the following: “He (Goethe) did not wish only to observe what is accessible to sense-perception; he strove at the same time towards a spiritual content which allowed him to determine the essential nature of the objects of this perception. This spiritual content through which a thing emerged for him out of the dullness of sense-existence, out of the indeterminacy of external beholding, and became something clearly determined in its nature (animal, plant, mineral) was called by Goethe Idea” (GA 30, p.270).

According to Goethe, the idea is not identical with sense-experience in its immediately given character, and true cognition consists in distancing oneself from this. On the other hand, Goethe does not, so Rudolf Steiner says in his book ‘Goethe’s World-View’, appreciate “any theory that wishes to be conclusive once and for all and is meant in its existing form to represent an eternal truth. He wishes to have living concepts through which the spirit of the individual draws together in his own individual manner the way things are beheld** (emphasis G.A.B.). To know the truth means, for Goethe, to live in the truth. And to live in the truth is nothing else than to take note, in the observation of every single thing, of what inner experience arises when one is standing before this thing. Such a view of human cognition cannot speak of limits of knowledge, of its being restricted by the nature of the human being” (GA 6, p.66 f.).

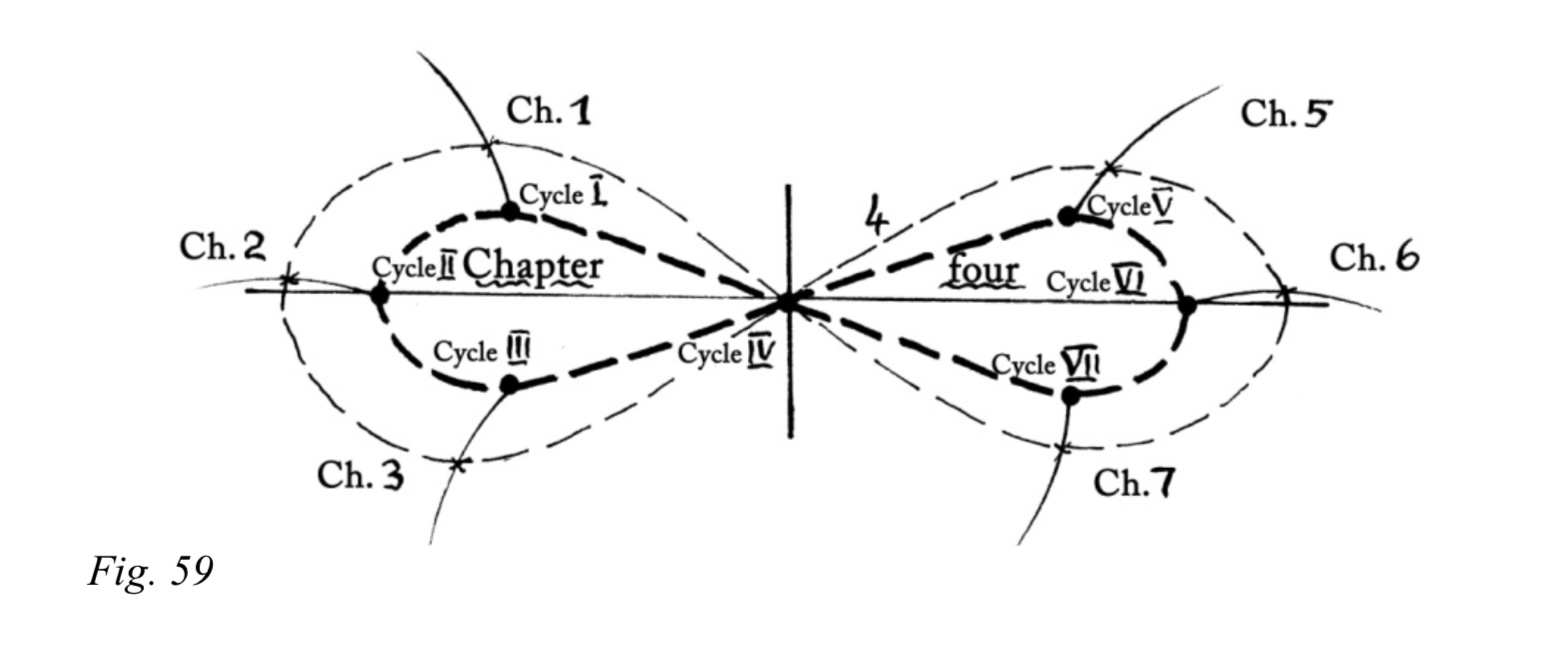

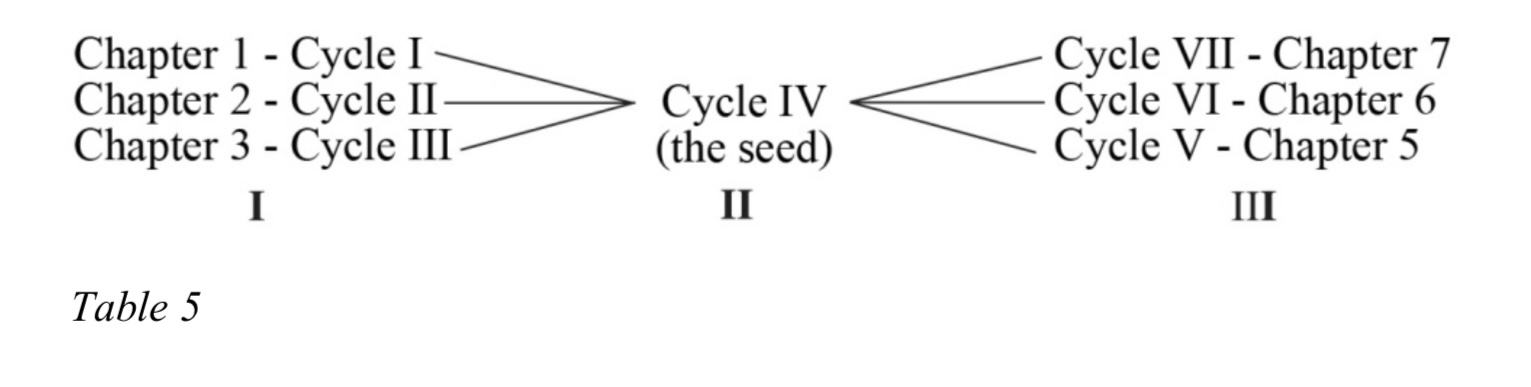

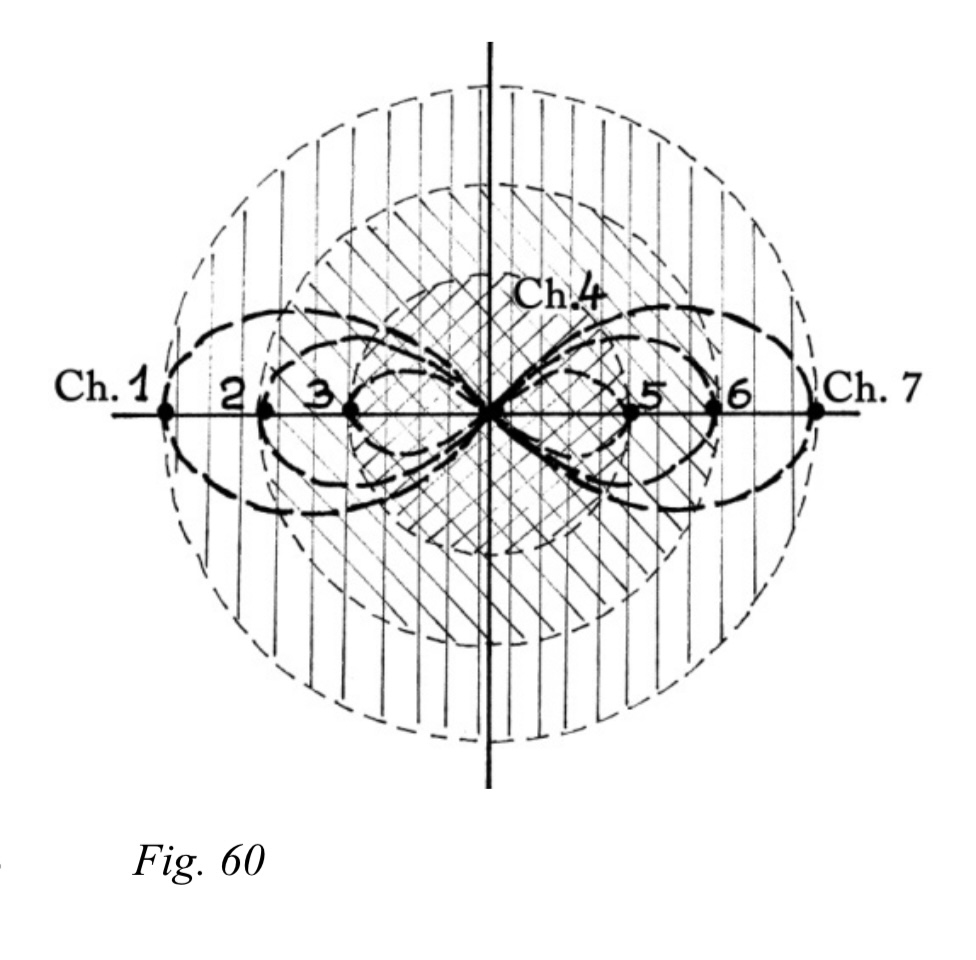

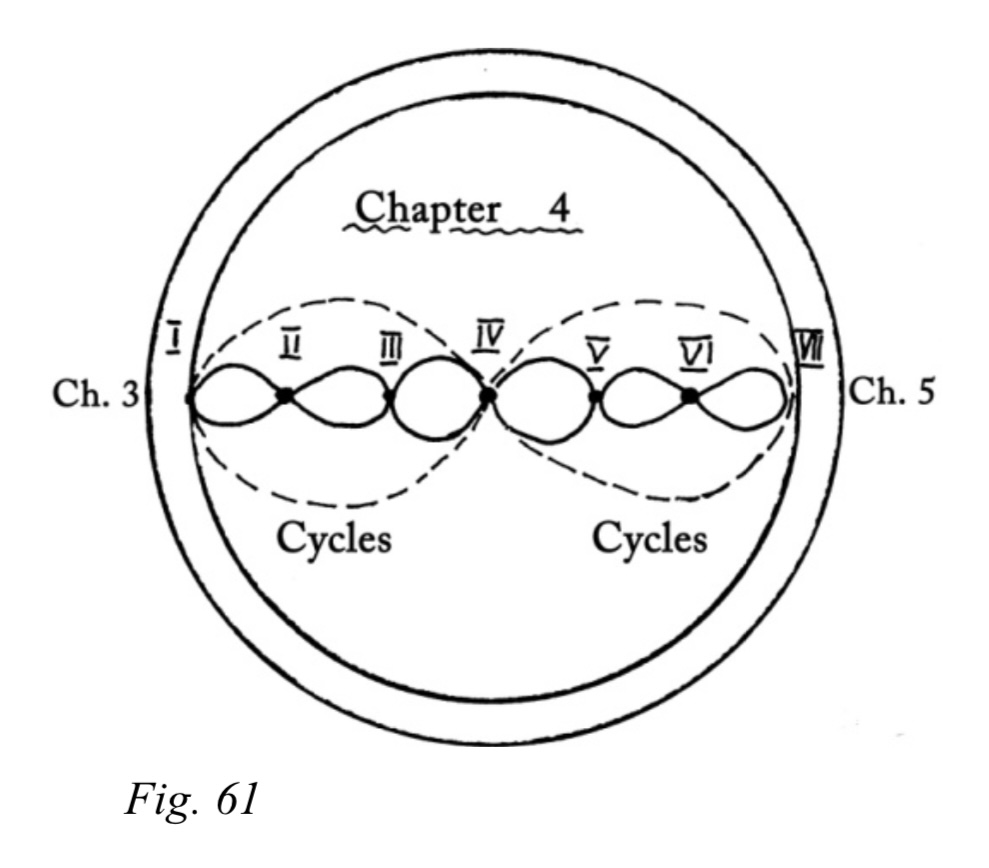

**

This

corresponds to the sixth element in our

sevenfold lemniscate of the thought-cycle.

________

Such, therefore, was Goethe’s answer to the fundamental question posed by Kant: What is knowledge? Goethe substantiated his answer through his own experience, as he had, on a practical level, developed within himself the capacity of ideal perception, of ‘beholding’. This is only possible if one metamorphoses the instrument of thinking into an instrument of ideal perception. In this way, Goethe laid the foundation, through transforming himself in practice, for that gigantic metamorphosis of the human species, thanks to which world-evolution enters a quite new phase. Rudolf Steiner was able to describe this event from the standpoint of modern science and in a scientifically comprehensible manner.

And he did not content himself with merely giving a description. Through incorporating Goethe’s teaching into its methodological foundation, Anthroposophy goes considerably further than Goethe himself. This is evident from its content as a whole. In the same book, ‘Goethe’s World-View’, Rudolf Steiner speaks of this himself when he compares Goethe with Hegel. Hegel felt himself to be a philosopher of a thoroughly Goethean kind, as one may clearly gather from a letter he wrote to Goethe on the 20th Feb. 1821. The affinity of the two thinkers’ ideas is seen in their approach to the principle of metamorphosis. In his observations Goethe came right up to the boundary where the sensible-supersensible phenomena of the plant-world are revealed and the idea comes towards the researcher. And yet: “In what relation the ideas stand to one another; how within the ideal realm the one proceeds out of the other; these are tasks of investigation which only begin on the empirical height where Goethe advances no further” (ibid. p.205).

According to Goethe, the multiplicity of manifested forms of the idea can be traced back to a fundamental form, a unitary idea, since they are all identical in their true and essential nature. So Goethe thought, but he left to the philosophers the solution of this problem. And Hegel was a philosopher who did research into the metamorphosis of ideas, as they move from their “purely abstract being to the stage where the idea becomes immediate and real manifestation. He sees as this highest stage the phenomenon of philosophy itself, since it is in philosophy that the ideas which work actively in the world are beheld in their own original form” (ibid, p.206). But Hegel had, just as little as Goethe, access to the immediate, imaginative perception of the ideas; neither of them even considered it. Rudolf Steiner concludes that the very fact “that Hegel sees in philosophy the most perfect metamorphosis of the idea, proves that he is as far removed as Goethe is from true self-observation.... But philosophy contains the ideal content of the world, not in the form of life, but in the form of thoughts. The living idea, the idea as percept, is given to human self-observation alone” (emphasis G.A.B.) (ibid). The shortcomings in the world-views of Goethe and Hegel were remedied by Rudolf Steiner through the new step taken by him in the theory of knowledge, which (in addition to much else) he illustrated in the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. He combined his argument in favour of the principle of freedom from presupposition in epistemology, with self-observation, suggesting to those who wish it, that they should repeat his experience themselves and grasp the far-reaching consequences arising from it. Firstly, a metamorphosis of consciousness begins to take place in the subject of cognition, leading to the development of a thought-sense which makes possible for him an immediate perception of the idea. And secondly, the process described leads to the resolving of the question as to how consciousness can be imbued with being, thus enabling – and this is the third point – human freedom to begin.

Without insight into the innermost essence of the world of ideas, neither Goethe nor Hegel was able to develop a view concerning human freedom. For this reason Max Stirner reproached them for their “glorification” of the dependency of the subject upon the object. Rudolf Steiner has shown how the content of the world can find its highest expression in the human personality. But in order to understand this rightly, one must first remain for some time on the heights of Goethe’s and Hegel’s achievement and experience the non-completion of their search. In one of his lectures Rudolf Steiner says the significant words: “....we can best find our way into this modern spiritual life if we try, through using the instrument of Hegel, to encompass the great spirit and the great soul of Goethe” (GA 113, 28.8.1909). In the conditions of our own time the best approach for us is to use Hegel and Goethe as instruments with which “to encompass” the teaching of Rudolf Steiner.

5. The Natural-Scientific Method of Goethe and

Rudolf Steiner

Regarding Goethe’s natural-scientific research it can also be said that it is methodologically free of prejudice. The method it applies is in the fullest sense of the word immanent to the object of study and free from conceptions and prescriptions that are dogmatic and have no root in experience. In his commentary to this research of Goethe, Rudolf Steiner draws out of it at least three methods. The first of them he calls “universal empiricism”. In accordance with this, Goethe remains in connection with the phenomenon and does not go beyond the limits of what is immediately given. This method requires one to give a precise description of the single particulars of the phenomenon. Goethe the researcher, who wishes to bring to light the causal connection between the phenomena, then moves across from universal empiricism to rationalism. He regarded both of these methods as limited and one-sided. The researcher has to use them to a certain extent, but then he must overcome them and apply the method of ‘rational empiricism’ which works with pure phenomena, these being identical with the laws of nature. The essence of this method is characterized as follows: “Because the objects of nature are separate from one another as phenomena, the synthesizing capacity of the spirit is needed, to show their inner unity. Because the unity of the understanding for itself is empty, the understanding must fill this unity with the objects of nature. Thus, in this third phase (the methodological – G.A.B.), phenomenon and spiritual capacity come to meet each other, and merge into one; and only this can bring full satisfaction to the spirit” (GA 1, p.190).

In his Goethe commentary, Rudolf Steiner built up at the same time his own methodology, in which the above-mentioned rational empiricism was able to unfold with a vigour unattainable to Goethe. From the beginning Rudolf Steiner places the main emphasis on the immediately given as the “what” of research, and not on the compliance with formal-methodological criteria. Scientific method betrays itself, when it places its reliance on abstract principles, sets itself unnecessary limits, and wrongly extends the monistic world-view into the sphere of methodology. Rudolf Steiner says of his own method: “Our standpoint is idealism, because it sees the ground of the world in the idea; it is realism, because it addresses the idea as what is real; and it is positivism or empiricism, because it wishes to reach the content of the idea not through construction a priori, but through approaching it as a given datum of experience. We have an empirical method which penetrates what is real and attains its final satisfaction in an idealistic result of research.... In our thinking there already presses up toward us what we wish to add to the immediately given. We must therefore reject any kind of metaphysics. Metaphysics wishes to explain the given with the help of something not-given, something inferred (Wolf, Herbart)” (ibid. p.182 f.).

Only a mind that is mistrustful of concepts will suspect that there is something eclectic in such an approach to the methodology of research, and only a consciousness that is free of prejudice will recognize the immense possibilities contained in it. When we have grasped it theoret- ically, only half our work is done. The method reveals its power through the realization of a certain cognitive experience, which does not, of course, in any way exempt us from the task of understanding the method itself.

Parallel to his commentary on the natural-scientific works of Goethe, Rudolf Steiner wrote the book ‘Outline of a Theory of Knowledge of the Goethean World-View’. This stands in the same relation to the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ as, for example, Hegel’s ‘Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences’ to his great work, the ‘Logic’, if we may venture the comparison. With regard to what we have said about the methodological principles of Anthroposophy, one can read in Rudolf Steiner’s book the following: “Thinking has access to that side of reality, of which a being of mere sense-perception would never have any experience.... Perception through the senses presents us with only one side of reality. The other side is the comprehension of the world by means of thinking.” “When we bring our thinking into activity, only then does reality receive its true determination (Bestimmungen)” (GA 2, p.63, 66). This should not lead us to think that we have to do with two sources of knowledge. There is only one such source, and that is experience in a wider sense, as the mediator between the subject, which feels the need to stand over against sense-experience in thinking, and the object, which is revealed to the outer senses; here, the subject can, in the process of spiritual, cognitive activity, raise itself to the experience that it is revealing itself to itself. And the ascent through the stages of cognition can become an ascent through the levels of consciousness.

General empiricism is the method we use in our work with the experience of direct sense-perceptions – sound, smell etc. And in this situation we feel that we are standing with our thinking over against our experience. It would be more exact to say here that the subject stands in the middle between the experience of perceptions and thinking about it. In this position, the subject applies the method of rational empiricism and, with its help, discovers ideal connections between the objects of perception. Knowledge of the connections ascends through different levels (cf. Fig.2); it leads us up to knowledge of the law governing the phenomenon. For this reason the concept is an element that belongs as intrinsically to the sense-world as its other parts, although, unlike these, it does not come to outer manifestation. “Sense-perception is therefore not a totality, but only one side of a totality. It is that side which can merely be looked at. Only through the concept does it become clear what it is that we are looking at” (GA 1, p.281).

In his striving to gain knowledge of the essential nature of things, the agnostic places this behind the things. Thus arises the limits to knowledge. But when we think about the things, we merge together with their essential being; they no longer stand outside us. But in this case, all that the human being says about the essential nature of things is revealed in the world of his own spiritual experiences. This person or that might accuse this methodological position of anthropomorphism; but here one could also appeal to the authority of Locke, who described as objective the primary qualities of things, which (as opposed to the secondary qualities such as colour, taste etc.) one can count and measure: they are all anthropomorphic. The human being humanizes his inner representations of nature, in very truth. But only in this way does the inner nature of things acquire the capacity to express itself. On the other hand we need to realize that the subjective qualities, too, are “nevertheless the expression of the inner essence of the things” (ibid. p.337). For this reason there is no basis for the assertion that an objective truth, the ‘in-itself’ of the things, is unknowable. The truth, in so far as it is known by the human being, cannot but be subjective. But now the objective nature of the things is revealed to the perceptions of our senses; they now appear to us as they really are. Hence, Goethe says: “The senses do not deceive.” But we can wrongly interpret our sense-experiences. To understand such a reversal, in Anthroposophy, of the generally accepted concepts, we need to avoid the pitfall of the theory of sense-experience, which consists in the intention to place “everything of a perceptible nature either within the soul” or “outside the soul” (B. 34). Locke’s school of thought severed the living connection between man and nature. It deprived nature of all those qualities by means of which it makes itself known directly to the human soul, and hid them away within the soul; and as time went on it fell into a state of tragic uncertainty, as it could find no answer to the question: What is the actual source of these secondary qualities that arise within me?

In his essay ‘Goethe and natural-scientific Illusionism’, which is added as a commentary in Vol. III of the natural-scientific works of Goethe, Rudolf Steiner says: “The subjectivity can, of course, be determined by nothing other than itself. Anything that cannot be shown to be conditioned by the subject, should not be described as ‘subjective’. We must now ask ourselves: What can we describe as belonging inherently to the human subject? All that it can experience in relation to itself (an sich selbst) through outer or inner perception.... Actually, what is subjective is only the path that has to be travelled by the sensation before it can be spoken of as my sensation. Our organization communicates the sensation, and these paths of communication are subjective; but the sensation itself is not” (GA 1, p.255 f.). And nothing gives us the right to assert that we create sensations.

If we have received some impression or other through the medium of eye or ear, we can investigate various mechanical, chemical and other processes which follow this impression outside or also within our- selves. They all take their course in space and time. “I can,” says Rudolf Steiner, “certainly ask myself: What spatio-temporal processes are taking place in this thing while it is displaying to my vision (let us say) the attribute of the colour red?” These processes have the character of a movement, electric currents etc.; something analogous occurs in the nerves, in the brain. “What is conveyed along this entire path is the percept of red which we have just referred to. How this percept expresses itself in a given thing that lies somewhere on the path from the excitant to the perception, depends entirely upon the nature of the thing in question. The sensation is present at every place, from the excitant to the brain, but not as such, not become explicit, but in precisely the way that corresponds to the nature of the object situated at that place.” Thus I experience “nothing more than the way in which that thing responds to the action proceeding from the sensation, or in other words: how a sen- sation comes to expression in a given object of the spatio-temporal world (emphasis G.A.B.). It is by no means the case that a spatio- temporal process of this kind is the cause that produces the sensation in me....” The process is, itself, “the effect of the sensation within a spatio-temporally extended thing”. The sensation comes to expression, as it were, in all processes of the sense-world; as such it does not exist in this world “because it simply cannot be there. But in those processes I do not, in any way, have as a given factor the objective nature of the processes of sensation; I have only a form in which they come to mani- festation”. And the processes themselves which convey the sensations are also given to us as sensations – in perception. Thus “the perceived world is... nothing other than a sum of metamorphosed percepts”. The perceived thing itself brings a sensation to expression in the manner “that corresponds to its nature. Strictly speaking, the thing is nothing other than the sum of those processes in the form of which it manifests” (ibid. p.267 ff.).

Such, therefore, is the fundamental picture drawn by Anthroposophy of the nature of sense-perception, and it forms the basis of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. There is full agreement between this and those statements in the philosophical system of Nikolai Losski in which he deals with sense-impressions. He says: “According to intuitivism, the object that is visible to an observer (a cloud) is an extract from the trans-subjective world itself (the cloud itself in the original), which has, itself, entered the subject’s horizon of consciousness; the colour of the cloud is not a soul-condition of the observer, but an attribute of the cloud itself, the trans-subjective. There is no such thing as a substitution of the material object by a soul-picture in the mind of the observer, hence no riddling problem arises as to the transformation of material into soul processes.”134

In another essay included in the third volume of Goethe’s Natural- Scientific Works, Rudolf Steiner approaches from a still wider perspective the question of the nature of perception. To counter the possible accusation that he had taken sides with Heraclitus and thus forgotten the “enduring element within change”, the “thing-in-itself” existing permanently behind the world of percepts, “lasting matter”, he says there that we would need to introduce the category of time into our considerations and separate, within the percept, the content from the form of its appearance. In the sensation given to the subject they are merged into one, as there is no sensation without a content. And sensations take place in the flow of time, but in such a way that their content – i. e. the enduring, objective factor – has nothing to do with time. The important element in the percept is not the fact that something occurs at a given point in time, but the question what is occurring. The sum total of the determinations (Bestimmungen) expressed in all these ‘whats’ forms the content of the world. The different ‘whats’ enable us to recognize connections of various kinds in their different forms of manifestation and they condition one another reciprocally in space and time. This fact gives rise to the wish to conceive, behind the sum-total of events, something unchanging – unending, indestructible matter. “But time is not a vessel in which the changes take place; it is not there before the things and outside them. Time is the expression, within the sense-world, of the circumstance that factual events, from the point of view of their content, are dependent upon one another in a (temporal) sequence” (GA 1, p.272 f.).

We discover time thanks

to the fact that the essential being of some-

thing comes to manifestation. “Time belongs to

the world of appearance.” But it has “nothing to

do” with the essential being itself. “This

essential being can only be grasped ideally (in

the form of ideas)” (ibid. p.273). If we have

not understood this, we feel the need to

hypostatize time as a factor in the unfolding of

processes, and then an existence appears, which

is able to outlast all changes: indestructible

matter.

But in reality the only thing that is

indestructible is the essential

being of

the phenomenon (time itself is conditioned by

it).* 135 Therefore in his other

work – ‘Goethe’s World-View’ – Rudolf Steiner

arrives at the conclusion that the “truth (and

by implication also the essential nature of

things – G.A.B.) arises through the

interpenetration of percept and idea in the

human cognitive process... there

lives within the subjective that which is

objective in the truest and deepest sense” (emphasis G.A.B.) (GA

6, p.64). Rudolf Steiner goes on to quote the

following words of Goethe: “When the healthy

nature of man works as a totality, when he feels

himself in the world as within a great,

beautiful, noble and valued whole, when

harmonious satisfaction grants him a delight

that is free and pure, then the universe, if it

could experience itself, would jubilate at

having attained its goal, and wonder at the

pinnacle of its own becoming and being.”136

* In this connection it

is interesting to note that Kant, in his search

for the a priori principles of sense-experience,

thought that time is “the form of the inner

sense, i.e. of beholding of our self and our

inner state.” It is subjective, but deducible

from experience, and represents the a priori

formal condition of all phenomena. Thus Kant

virtually robs us in two ways of the possibility

of ascending from appearance to essential being

and takes refuge in metaphysics. This problem

cannot be solved if we do not rise from the

phenomenon to the ‘ur’-phenomenon.

________

The desire for knowledge arises in the human being and not out of the things around him. But when the human being is engaged in cognition, he is seeking, not for the ‘in-itself’ of things that will remain forever hidden from him, but for the balancing-out of two forces which approach him from two sides – through percepts and concepts. Without the human being such a process is impossible. How it should be carried out correctly, is a question dealt with by the Goethean theory of knowledge, which sees in this process the highest stage and the completion of the nature-process that has led to the forming of the individual principle within the world of otherness-of-being.

The act of cognition would not be necessary if the human being received something finished and complete through perception and observation. We observe a sequence of facts as something given; and moreover we come to know it in its givenness. But another, yet higher power of our spirit must reveal itself, so that the unending sequence of facts can be revealed on the level of the highest laws at work within them. And that which reveals itself in us in this case is a part of nature, only we create it ourselves. Thus we do not create the tone, the colour – they belong to outer nature and are objective – but we do create a higher, ideal part of nature.

The assertion that the world is nothing more than my inner representation has its source in the dominant role of the secondary qualities in our soul-life, and in an underestimation of the role of thinking in it. This assertion could be complemented by another: namely, that the human being is an inner representation of the world (the world-individual) with respect to the world’s primary qualities. For the sense-perceptions of the human being are not given to the world-subject. But the human being is able to have both kinds of inner representations and in this way to attain to a unitary reality, which is given in thinking and perception. Geometrical (spatial) and other mathematical conceptions, the ideas of force, of gravity – all these are observed by the human spirit which ‘beholds’ the ideal relations between the percepts. They are, as the medieval Scholastic would have said, “the essential forms within things”, from which they are liberated thanks to the human spirit. But in this case there can be no doubt that the human being as an inner representation of the world is also the “thing-in-itself” of this world, if the world has the capacity to know itself (and it has).